Sensory processing is the first way children have to understand and experience the world around them. When sensory processing is not going well for a child, many challenges can present themselves from picky eating to behavioral issues. Melissa Haas, an Occupational Therapist specializing in pediatrics, met with Cole to discuss how we can promote good sensory development in our young kids.

What is Sensory Development?

First, it is necessary to understand what sensory development is. As Melissa explains, it is the integration of information from the sensory systems:

- Proprioceptive – input from joints and muscles

- Tactile – input from touch

- Visual – input from what is seen

- Auditory – input from hearing

- Vestibular – input received from the connection from inner ear to central nervous system that coordinates movement with balance.

Long before cognitive processing helps young children understand their environment, sensory input is telling them all about the world around them. The process starts at birth and is the main processing tool children have until about the age of 3. Sensory processing has multiple layers and levels and is truly a lifelong process. However, starting at birth, Melissa points out that because infants have so little control over their bodies, parents start out with a lot of sensory control: temperature, what touches a baby’s skin, and so much more.

First Sensory Inputs

Because parents control so much of what an infant experiences, Melissa notes that tummy time cannot be over-emphasized. Ideally, the first tummy time occurs soon after birth – possibly in the form of skin-to-skin contact with a parent in a semi-reclined position. And tummy time remains a critical tool at home. In tummy time so many sources of input are available:

- Tactile input on the face (which is very sensitive) from the blanket or surface the infant is laying on.

- Neck and core muscles are developed as a baby begins to lift its head.

- Visual system is developed as a baby moves its head to change what is being seen.

- The vestibular and proprioceptive systems develop as a baby starts to be able to push themselves up on their hands.

Babies on the Move

The development of these systems continues as babies begin to move, as well. Melissa points out that infants begin to control responses to input during this phase. For example, if an infant is crawling and doesn’t like a crumb that he or she touched with their hand, they move their hand away. It is simple but so important to develop connections between what is experienced in the world and how we respond to those experiences. During the movement phase of infancy, more significant input occurs:

- Tactile input from what hands touch and from moving hands. This also leads to fine motor development that is used in eating, handwriting, and more.

- Rolling targets vestibular system – understanding where the body is in time and space

- Crawling (reciprocal motion of the arms and legs) uses many systems and stimulates multiple parts of the brain simultaneously. Proprioceptive and vestibular input are received for movement and balance, tactile input from a variety of surfaces being touched, and visual input is received as infants look around and adjust from looking close to farther away. Crawling is also closely linked to reading ability and other academic pieces, Melissa notes.

Another area for sensory development outside of movement is food. The introduction of foods during the first few years of life is a huge source of sensory input for the oral and tactile systems. Melissa notes that many well-meaning parents wipe their children’s hands and face practically after every bite, but that food is really meant to be messy. Messy means that the child is exploring their food – the experience of food – and it is important to overall sensory development. Melissa recommends putting a child in a high chair with a shower curtain or mat underneath and letting the exploration begin.

When Things Are Feeling Hard

What if sensory input or response is not going well in those first few years of life? Does a child have significant difficulty tolerating daily activities of life: dressing, hair washing, nail clipping, or teeth brushing? Does a child have entire food groups that they will not eat? Is a child super clumsy – struggling to understand their body in space? Are there significant behavioral/emotional/self-regulation issues that prevent the family from moving through normal activities? These are some of the common challenges that Melissa helps children and families with daily. Melissa notes that sensory development is a lifelong process so there is always room for improvement. Melissa recommends the following process if a family notices a challenge at home and is not sure what to do next:

- Ask “how big is this problem in the life of the family”? If these challenges prevent the family from doing normal activities, Melissa recommends seeking resources such as:

- “Zones of Regulation” to help children develop language to understand their body and feelings. She notes that it is appropriate to have a range of emotions throughout the day, and learning how to appropriately communicate and respond to those feelings is one way to help children struggling with sensory processing.

- Another tool is offering kids breaks between transitions or times when things are starting to feel hard/out of control. “Heavy work” such as jumping on a mini trampoline can help kids regulate at these otherwise challenging times.

- Try to understand triggers – is there a certain transition that always feels hard? Is there a certain task that is always a struggle? These clues can give insight into the underlying cause of dysregulation.

- Use language to validate feelings and emotions. When a kid falls or bumps his head, a parent might say “Oh, that must really hurt.” instead of “It’s okay. No big deal.”

- Melissa recommends talking to the child’s pediatrician or primary care physician, if simple changes aren’t helping the family get through normal activities or a child’s ability is impeded.

- If there is not a medical issue causing the difficulties, a physician may refer the child to an occupational therapist for evaluation.

We all have times when we feel overwhelmed by the world and the set of circumstances we are experiencing. Our young children have not yet developed the language or cognitive processing to put those experiences into words which is why the occasional tantrum is expected. However, if a child is struggling with sensory processing, common activities can send them into fight or flight mode. In those cases, when daily activities are significantly challenging, addressing sensory processing may be a useful avenue to improving the quality of life for the family as well as the child’s ability to successfully navigate the landscape of life.

Recommended resources:

- “Raising a Sensory Smart Child” by Lindsay Biel & Nancy Peske

- “No Longer a SECRET” by Doriet Bialer and Lucy Jane Miller

- “The Superkid’s Activity Guide to Conquering Every Day” by Dayna Abraham

Meet Melissa Haas

Melissa has degrees in Philosophy and Occupational Therapy from Mount Mary University. She has spent her career working with children and holds specialized training and certifications in Sensory Integration and Handwriting Without Tears. Melissa has a passion for working with children who are facing sensory processing and/or mental health challenges. She has seen firsthand how helping children understand their challenges and body can make lasting impacts on the child and parent-child relationship. Melissa also enjoys running, travel, and outdoor activities with her husband and two sons.

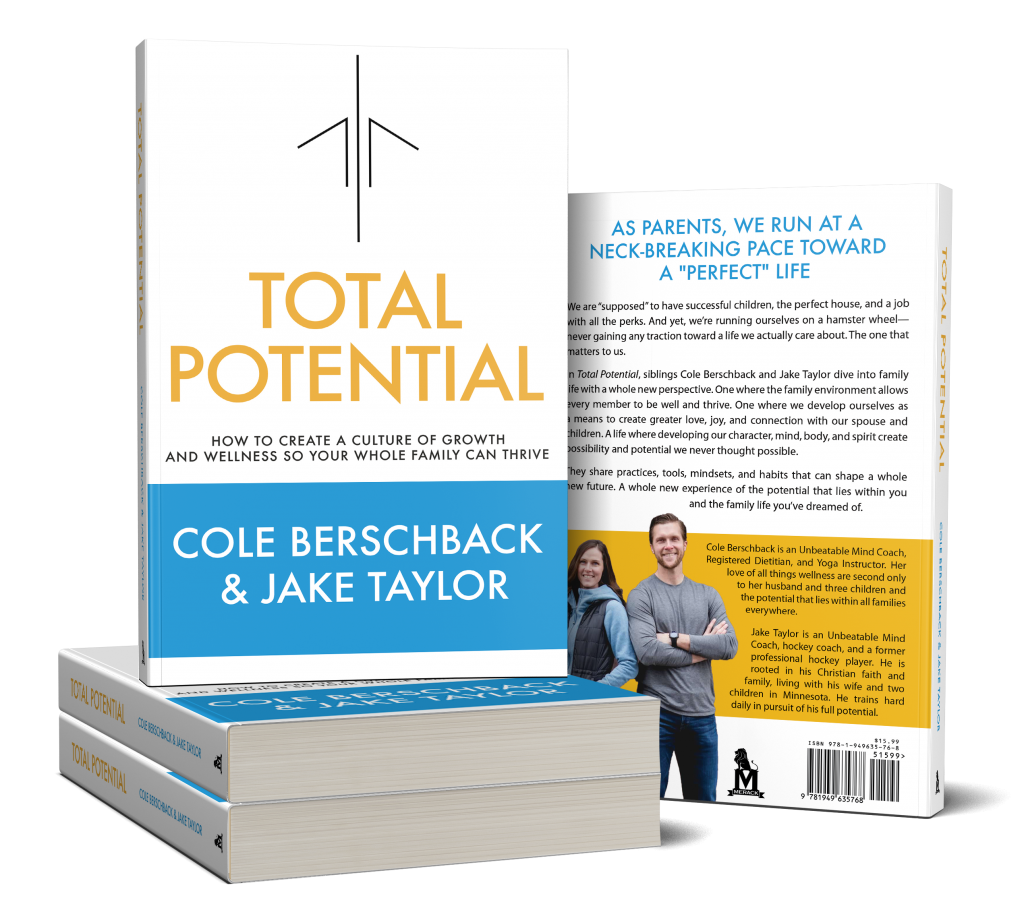

Cole Bershback

Cole is a wife and mom of three. As a Registered Dietitian, certified yoga instructor, and Unbeatable Mind Coach, she has committed her life to wellness and the pursuit of our highest potential. If grit and love had a child, it would be Cole Bershback.